Roger Williams and the Birth of Religious Tolerance in America

- Robert Farago

- Mar 14, 2024

- 5 min read

Updated: May 8, 2024

America's (mostly) forgotten Founding Father

Religious tolerance is enshrined in the First Amendment of the United States Constitution. Passed on December 15, 1791, the first words read…

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.

Yes, well, the idea that the United States began life as a safe sanctuary for religious separatists living together in peace and harmony – ye olde melting pot – is a myth.

The Smithsonian article America’s True History of Religious Tolerance sets the record straight.

From the earliest arrival of Europeans on America’s shores, religion has often been a cudgel, used to discriminate, suppress and even kill the foreign, the “heretic” and the “unbeliever” — including the “heathen” natives already here.

Kenneth C. Davis ain’t just whistling Dixie! Not that anyone would these days, but you know what I mean. If not…

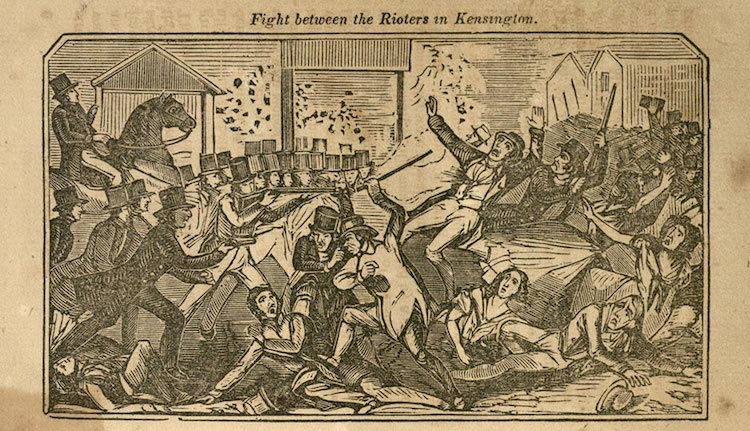

North America’s Bloody History of Religious Conflict

Mr. Davis traces religious intolerance in North America back to its earliest, pre-colonial past. It’s a fascinating story, but it sure ain’t pretty.

In 1565, established a forward operating base at St. Augustine and proceeded to wipe out the Fort Caroline colony. The Spanish commander, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, wrote to the Spanish King Philip II that he had “hanged all those we had found in because...they were scattering the odious Lutheran doctrine in these Provinces.” (111 frenchmen killed) When survivors of a shipwrecked French fleet washed up on the beaches of Florida, they were put to the sword, beside a river the Spanish called Matanzas “slaughters”(134 frenchmen killed). In other words, the first encounter between European Christians in America ended in a blood bath.

You might say Commander Avilés’ execution of French sailors and settlers set the standard for religious tolerance in North America, and you wouldn’t be entirely wrong.

If you thought North America immigrants escaping religious persecution in Europe were sympathetic to others in the same but different boat, you are wrong.

Christian Mingle it Wasn’t

While it is true that the vast majority of early-generation Americans were Christian, the pitched battles between various Protestant sects and, more explosively, between Protestants and Catholics, present an unavoidable contradiction to the widely held notion that America is a “Christian nation.”

Christians killing Christians is still Christian (if not very Christ-like). And while it’s certainly true that the majority of our Founding Fathers were Protestants, American Christians had no lock on religious intolerance.

The Smithsonian article chronicles more than two hundred years of religious persecution in the latter day United States – both legal and homicidal. Afflicting Jews, Catholics, Mormons, Muslims and Quakers. To name a few.

In fact, it’s something of a miracle that religious tolerance became a Constitutionally guaranteed right, if not a practical reality.

Props to Washington, Jefferson, Adams and Madison. Founding Fathers who held religious tolerance and secular government in the highest possible regard. But they were not the philosophy’s first champions on North American shores.

Roger Williams

If you’re looking for the man who first brought religious tolerance and secular governance into practical effect in the New World, Roger Williams is your man.

Born in London around 1603, Williams attended Pembroke College in Cambridge. Renowned for his linguistic skill, ordained by the Church of England, Williams was a trouble-making free thinker, an ambitious man who identified with Puritan separatists.

Disillusioned with the Church’s doctrine and political power, Williams emigrated to Boston in 1630. His anti-establishment sermons didn’t find favor in Boston. After two relatively peaceful years preaching in Salem, Williams moved to Plymouth – back into territory controlled by the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

The Colony’s leaders were none-too-happy with Williams’ antipathy towards organized religion’s autocratic control. Williams turned to fur trading with native tribes, learning their languages, befriending Wampanoag Chief Massasoit. Continuing to preach where and when he could.

In 1636, the General Court of Massachusetts had enough of Roger Williams. They banned him from the Colony for sedition and heresy. His crime: promoting the idea that civil authorities shouldn’t be able to punish religious dissent or confiscate Native lands.

\

As Williams had fallen ill, the Court allowed him to remain in Massachusetts until spring – on condition that he stop preaching “diverse, new, and dangerous opinions.”

\

Williams didn’t stop. Facing arrest, the English preacher walked some 50 miles through deep snow into present day Rhode Island, sheltering in the safety of a Wampanoag winter camp.

Rhode Island’s Radical Religious Right

To establish his own enclave, Williams bought a tract of land from the Narragansett natives. He gathered a small band of followers who shared his belief in religious tolerance and secular authority.

In 1644, eight years after his expulsion from Massachusetts, Williams returned to the UK to petition King Charles II, seeking to establish the colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations.

Almost twenty years later, on July 8th 1663, King Charles finally granted Williams and his followers a Royal Charter. As a Catholic sympathizer in a mostly-Protestant England, the King granted Williams’ request to guarantee settlers religious freedom within the Colony.

No person within the said Colony, at any time hereafter, shall be any wise molested, punished, disquieted, or called in question, for any differences in opinion, in matters of religion, who does not actually disturb the peace of our said Colony; but that all and every person and persons may, from time to time, and at all times hereafter, freely and fully have and enjoy his own and their judgments and consciences, in matters of religious concernments, throughout the tract of land heretofore mentioned, they behaving themselves peaceably and quietly and not using this liberty to licentiousness and profaneness, nor to the civil injury or outward disturbance of others.

The Charter’s religious provision was unprecedented: a revolutionary innovation in colonial governance that came to be known as “the lively experiment.”

Safe Haven for Religious Refugees

The Charter affirmed and formalized well-established practice within Roger Williams’ aspiring colony. For example…

In June 1661, more than a dozen Quakers released from Massachusetts prison found refuge in Rhode Island. And there they remained, unmolested, despite neighboring colonies urging Rhode Island to rid itself of the “notorious heretics.”

Around 1658, persecuted Jews found safe haven in Newport, establishing the New World’s first synagogue in 1763. They worshipped aside and did business with Baptists, Antinomians, French Huguenots, atheists and more.

Roger Williams was the Colony’s Governor from 1654 through 1658. In his seventies, during King Philip's War, he saw almost all of Providence burned to the ground. And lived to see it rebuilt.

Throughout his stewardship, Williams worked to maintain peace between colonists and natives alike. Through it all, he protected the principle of religious tolerance and the separation of church and state.

The Union of the State

The idea that people holding different religious views should live together peacefully was hardly new.

What made Williams’ Rhode Island different: the Colony proved that a multi-religious secular state could be a success. Again, a lesson that many colonies and, eventually states, ignored. At great cost to all.

Even so, there’s no question that the men who shepherded the First Amendment into being were inspired by Roger Williams’ and his compatriots’ “lively experiment.”

Although Williams was buried with little fanfare 108 years before the United States Constitution was ratified, his legacy is one of America’s finest inheritances.

Williams’ history sends a clear message to present day America: live and let live is not only the right thing to do, it is, and always should be, the law of the land.

.png)

Comments